Most people are familiar with the growth rings seen in tree cross-sections, but few are aware that similar growth patterns are visible in skeletons of reef-building corals.

Coral Skeleton Growth

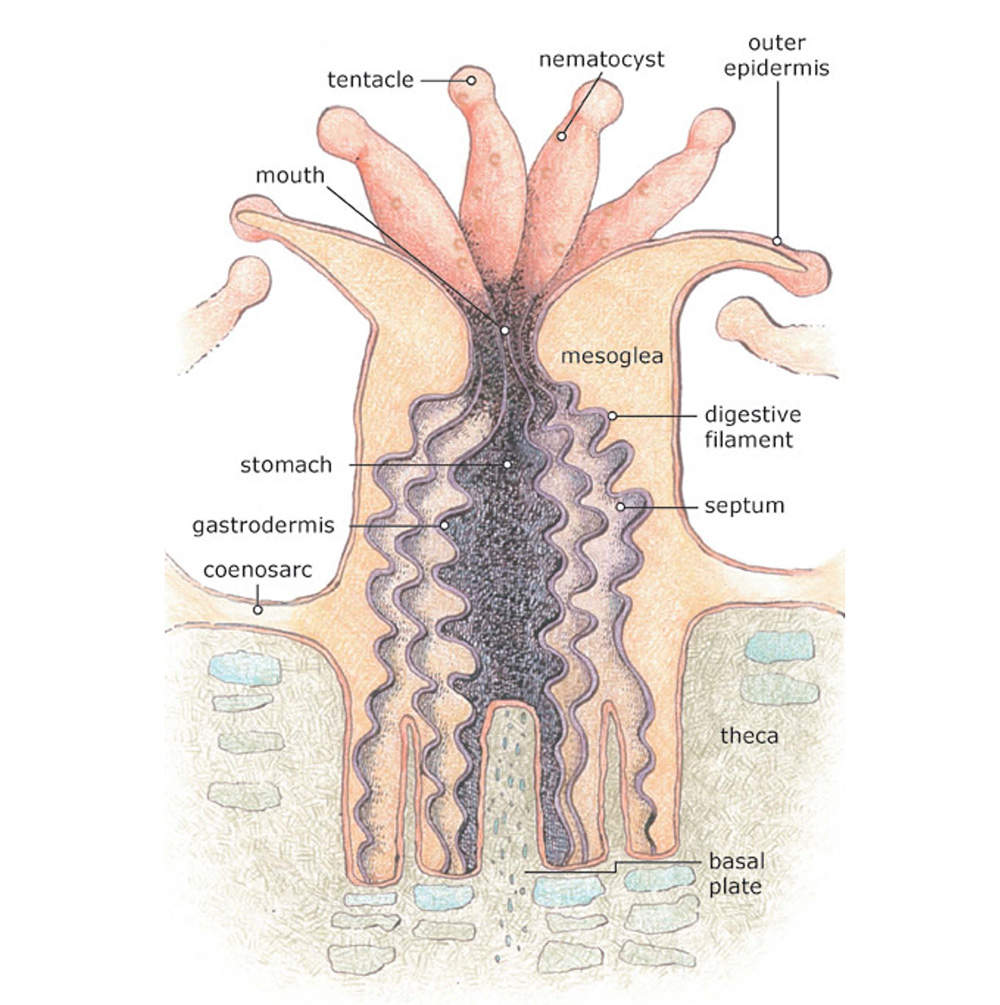

Beneath the thin layer of living tissue at the top of a coral colony, the polyps of reef-building corals lay down hard layers of calcium carbonate. This is what we consider the hard, or stony, part of the reef--the coral skeleton.

As coral colonies grow, the structure and chemistry of these layers is affected by variations in the temperature and water composition around them. This makes them suitable climate proxies. In other words, the information in their layers can tell us what the local climate was like at the time they were created.

At Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, scientists have determined that coral skeletons tend to grow more rapidly in fall and winter months, when temperatures are more moderate (72-77F or 22-25C). When temperatures are closer to the corals' outer tolerance levels (68F and 84F or 20C and 29C), growth is slower. The result is an identifiable series of growth bands.

Coral Coring

In order to see these layers, scientists drill cores out of large coral heads. This gives them a look at many years-worth of layers in one compact unit. The larger the coral colony, the more years of data they can extract.

These are the cores that were extracted from the mountainous star coral above. (Photo: Emma Hickerson/FGBNMS)

Core Analysis

X-rays of coral cores make it easier for scientists to examine the annual growth bands in reef-building corals. Dark bands show the slow, high-density growth that takes place during the summer. Lighter bands show the faster, low-density growth that takes place during the winter.

Scientists can take a look back in time to determine when temperatures were warmer or cooler, by simply examining the depth of each growth band. Larger low-density bands indicate warmer winter temperatures. Slightly darker bands, known as stress bands, indicate periods of environmental stress, such as temperature extremes. (see labeled image above)

Within each band scientists can also evaluate the chemical content (stable isotopes) to learn more about atmospheric conditions. By drilling out 12 tiny samples from each growth band, they can examine the oxygen and carbon isotopes to determine specific temperatures during each month of the year.

The image to the left shows x-rays of two coral core samples extracted from colonies of Orbicella faveolata (previously known as Montastraea faveolata) and Siderastrea siderea at East and West Flower Garden Banks in 2005 (Credit: FGBNMS/TAMU).

Scientists from Texas A&M University analyzed these core samples to identify patterns in growth over periods of time. They then compared these to what we know of air and water temperature readings in the region to help them evaluate cores that go back farther than recorded data and "read" climate history.

This gathering and analysis of climate data from natural recorders such as coral skeleton layers, tree rings, ice cores, etc. is known as paleoclimatology.

Why do we want to do all of this? Understanding how climate has affected the Gulf over a period of years, decades, or even centuries may help us recognize and anticipate future changes, so that we can appropriately manage our marine resources.

Coral Cores Lesson

An educational lesson using x-ray images from sanctuary coral cores, along with many other lessons and activities, is available from the For Teachers page of this website.